In 2019, the City of Berkeley accomplished what few could do before: it passed a city ordinance to reduce single use disposable foodware and litter.

The Ecology Center teamed up with local, national, and international nonprofits to discuss the problems with plastic within the food system – its ubiquity, its environmental and human health harms, its financial strain on businesses, consumers, and the City – and launched a community-driven campaign to make improvements.

The Single Use Foodware and Litter Reduction Ordinance, which is a first-of-its-kind-policy, was developed out of deep collaboration with stakeholders across the City to include multiple waste and litter reduction strategies, including updated waste bins and signage, a charge on single use cups, and requiring on-site dining on reusable foodware.

This webpage is designed to document what we did in Berkeley and to inspire others to make similar changes in their community. For a step-by-step guide on how to fight for reuse policy, check out Upstream’s Roadmap to Reuse toolkit or email Macy Zander, Upstream’s Reuse Communities and Policy Engagement Officer, at macy@upstreamsolutions.org.

- Concerned residents and local activists coalesced to create and pass an ordinance to curb the amount of single use disposable foodware waste generated in the City of Berkeley.

- The ordinance aimed to avoid replacing one disposable foodware material (e.g., plastic) with another (e.g., paper) and foster overall disposable foodware reduction and foster reusable foodware.

- There were four baseline agreements and understandings when creating the policy: 1. It is acceptable to food vendors; 2. It is feasible to pass, implement, and enforce; 3. It is built on the successes and learnings of previous anti-disposable legislation like our carryout bag reduction laws; and 4. It is comprehensive so it could be used as a model ordinance for other jurisdictions worldwide.

- There were numerous challenges – both anticipated and unanticipated – which resulted in more adjustments to the ordinance language.

- To make the transition easier for all parties, the final ordinance contained a three-phase approach that addresses making reusables more economical and accessible, as well as disincentivizing disposable foodware.

- The ordinance was unanimously passed by the City Council. Many contributing factors were location agnostic: the overall campaign structure (initiate, build, close), having a multidisciplinary team, engaging all stakeholder groups early, doing a cost savings analysis for Councilmembers opposed to the ordinance, getting a Councilmember as a ‘champion’, and determining priorities especially as it pertained to negotiations.

History of Ecology Center & Plastics Recycling

The Ecology Center started the first curbside recycling collection in the nation in 1973 and is Berkeley’s contracted recycler. For decades we have worked on plastic reduction strategies and challenged false narratives about plastics recycling. In the 1980s we vocally opposed the move from refillable glass bottles to plastic ‘recyclable’ bottles under California’s bottle bill, citing the shift from a circular reuse program to a linear downcycling system with massive fossil fuel and toxic implications. Also during the 1980s we supported efforts to fight ozone depletion through a ban on expanded polystyrene takeout foodware, perhaps the first Styrofoam ban in the US. Furthermore, in the 1990s, we resisted the collection of plastic bottles as the markets were limited and highly suspect.

Under pressure from the plastic industry’s campaigns, City Council and community members pressured us to revisit plastic recycling in the 1990s. With support from the City Council to study plastic recycling, we formed the Berkeley Plastics Task Force pulling together civic leaders, recyclers, chemists, and advocates to study plastic recycling and make recommendations back to the City Council. This Task Force released the Report of the Berkeley Plastic Task Force in 1996 debunking many plastic and packager myths and identifying that while there were downcycling markets for #1 (PET) and #2 (HDPE) bottles, there were no viable markets for any other mixed plastic packaging (#3-7). The report also identified the upstream and toxic implications of plastic packaging that were available at the time. Following the report and a brief pilot, Berkeley began accepting #1 and #2 bottles and jugs.

Industry Driven “Collect All Plastics” Programs Expand

By the early 2000s many cities in California had caved to pressures from the plastic industry by adding all rigid plastic packaging to their recycling programs. The argument by the industry at the time was that if you collect it all you will get more of the #1 and #2 bottles and jugs and that eventually there will be markets for the rest of the plastics collected. Many programs also experimented with collecting film plastics in ‘bag the bag’ programs where customers collected plastic bags in larger plastic bags and then placed them in their curbside bins. International markets for both of these streams temporarily emerged in China and other Asian nations as their fast-growing economies needed the feedstock to keep up with production demand. The Ecology Center was getting reports from our colleagues at the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA) (at the time fiscally a sponsored project of the Ecology Center), of massive dumping and burning of plastic and oppressive and hazardous labor conditions in the informal sectors, causing irreparable harm to communities in China and elsewhere as a result of US mixed plastic exports.

Despite this, and due to ongoing campaigns by the plastic industry and an ever-increasing expansion of plastic packaging that industry sold as recyclable, more and more of these mixed rigid containers (#3-#7 plastics) were being put in recycling carts by well-intentioned residents. During the 2000s the Chinese informal sector markets for these mixed rigid containers grew rapidly. They were able to cheaply sort these mixed grades and recycle a small percentage of them while dumping and burning the rest.

We identified key environmental and labor concerns with these markets as a general guideline for acceptable markets to sell mixed plastics. These guidelines included meeting the labor laws in the destination country, having at least rudimentary wastewater treatment systems for the washing of plastics, ventilation and air filtration systems for extrusion and pelletizing, and documented safe disposal of non-recyclables in regulated landfills with no incineration of residual plastics. As these conditions were not available in the mixed plastic export market, and no US market existed, we did not include mixed #3 – #7 plastics in Berkeley’s collection program.

China’s Mixed Plastic Markets Grow

By 2010 most of the cities around the Bay Area were collecting and exporting these materials through single-stream recycling programs, meaning all recyclable material (e.g., plastic, glass, metal, paper) was commingled in one cart versus being separated. We support efforts to increase collection efficiency and reduce worker risk for injuries, such as the use of curbside rolling carts and more operational automation. However, mixing all recyclables together incentivizes ‘wishcycling’, increases sorting costs, and produces highly contaminated scrap commodities. While single-stream allowed for a massive expansion of recycling programs across the state and nation, it produced lower-quality materials.

At the same time, China built new processing facilities that were state-of-the-art and designed to take post-consumer mixed materials. For instance, the old US mills were built for virgin paper pulp from old-growth forests, but China’s new mills could handle dirty materials, needed massive amounts of feedstock, and were paying top dollar. China’s informal sector also started buying up any plastic they could find across the globe with little regard for quality, and California exports of plastic scrap soared between 2005 and 2015.

Nonetheless, we insisted on keeping paper and glass separate and rolled out a dual-stream split-cart program that ensures high-quality paper and other materials, keeps processing costs low, keeps contamination low, and forces residents to think about what goes in the recycling bin.

…The argument was that if someone is paying for them, they must be getting recycled. We now know that … a very high percentage was being dumped or burned

The Ecology Center continued to hold off efforts to add #3 – #7 plastics to our collection program. Despite occasional concerns raised about the impact of low-grade exports, the argument was that if someone is paying for them, they must be getting recycled. We now know that while some of the mixed plastics were being sorted out and recycled, a very high percentage was being dumped or burned, thereby contaminating the air, soil, and groundwater, and polluting rivers and eventually the oceans.

Ecology Center Begins Collecting #3 – #7 Mixed Plastic Containers

Around 2010, we learned of a China-based recycling facility that claimed to meet the baseline requirements of adequate labor laws, working conditions, and environmentally sound management of waste of non-recyclable material. Leaning into the expert and trusted network of local Zero Waste organizations through GAIA, the Ecology Center contracted the WuHu Ecology Center to do a site inspection of the King Fong facility in Guangdong, China. The findings of this inspection confirmed that while this facility would not meet California’s strict environmental and labor standards, King Fong did meet our baseline requirements to safely recycle mixed rigid plastics.

Based on this direct market with a clear line of sight to the final destination and the transparency and accountability of working directly with this specific facility, in 2013, we reluctantly began accepting non-bottle mixed #3-#7 rigid containers (a subset of mixed plastics). This included plastic clamshells, deli, and dairy tubs, plastic cups, and a wide array of other container types – mainly from disposable foodware. At significant expense, Berkeley’s recycling processor, Community Conservation Center (CCC), made modifications to their sorting system to be able to handle these materials, and the Ecology Center expanded its fleet to add these high-volume but low-weight containers to its collection program.

China Pulls Back

Within a year of beginning the collection of mixed rigid plastics, China announced Operation Green Fence to clean up its recycling imports. This was an initial signal to the US (and other) exporters that China was intending to change course and stop accepting contaminated mixed recyclables. While Green Fence prohibited many materials coming from unscrupulous single-stream recycling programs it impacted mixed plastics the most. Seeing what was to come in this changing recycling environment, King Fong stopped purchasing mixed plastic bales and focused on cleaner post-industrial and domestic sources for plastic scrap. This left Berkeley without a reliable and responsible market for its non-bottle mixed rigid containers. Initially, these materials were sold to west coast brokers, who typically sell to brokers in Hong Kong. After that, there is no traceability of accountability for the final destination of the material or its end fate.

To better understand these markets, in 2015 we began to track shipments using newly available GPS trackers. We again relied on contacts through GAIA and the emergent #BreakFreeFromPlastic Movement for on-the-ground verification and inspection. What they found confirmed the worst mixed plastics were going to ever-changing destinations in the informal markets in China and Malaysia. Some of these shipments ended up in communities where unrecyclable plastics were dumped and burned, or at rustic facilities where there was no wastewater treatment, ventilation or air filtration systems, or labor standards.

It was clearer than ever that Berkeley needed to find a solution to prevent this waste in the first place, and that there is no way to recycle your way out of the plastic packaging crisis.

With this information, Berkeley stopped exporting mixed grades of plastic and began working with a pilot project in southern California operated by Titus MRF Services that was testing technology to mechanically sort mixed plastics using high-tech optical sorters, robotics, and artificial intelligence. They were able to capture approximately 50% of our mixed bales for recycling but disposed of the rest in a local landfill. While this was very expensive and produced marginal benefits, it was much better than exporting harm to other countries. Eventually, this pilot closed as they were not able to make it work financially. At this point, Berkeley began sending the bulk of these materials directly to the local landfill for disposal. It was clearer than ever that Berkeley needed to find a solution to prevent this waste in the first place, and that there is no way to recycle your way out of the plastic packaging crisis.

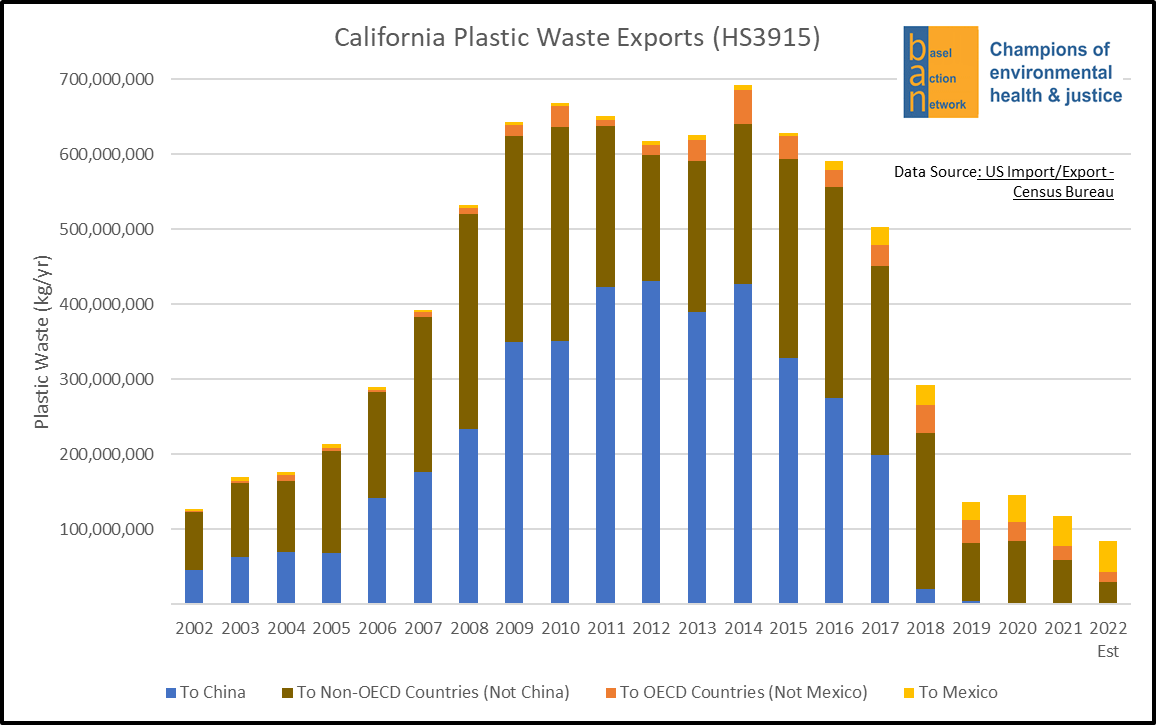

In 2018, China implemented its “National Sword ” policy prohibiting the import of mixed recyclables effectively terminating all US exports of plastic scrap to China. Immediately these exports were shifted to other Southeast Asian Countries that had even less capacity to handle them. In 2019, the Basel Convention – the international treaty that controls shipments of hazardous wastes across national borders – was amended to control the export of mixed plastics to member nations and most counties also passed new laws and enforced new standards to prevent the import of these grades, dramatically reducing California’s exports. While the illegal export of plastic scrap still exists and new questionable markets are emerging in Mexico, for all intents and purposes by 2020 there were no significant domestic or foreign markets for mixed #3 to #7 markets.

Figure 1: The above graph demonstrates California’s previously large reliance on exporting plastics (#1-7) to China (blue). Since China highly restricted the import of plastic material in 2018, California is shipping substantially less material abroad. The material that used to be exported is primarily landfilled or incinerated domestically as domestic recycling companies have not been able to account for the large change in demand. Source: Basel Action Network (2021), 2021 Annual Summary

The Problems with Disposable Foodware

The Rise of Single Use Disposable Plastics

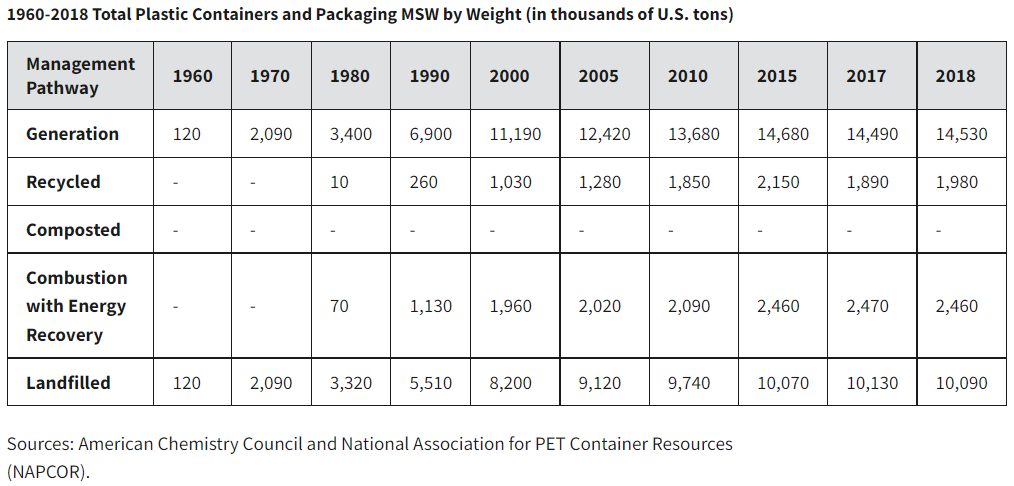

The main problem and galvanizing force to create a disposable foodware reduction ordinance was the fast-growing use of disposable foodware. In fact, plastic used for packaging – which includes disposable foodware – was the fastest-growing use sector since the 1960s (see Figure 2). Specifically in the US, between 1960 and 2018, 14.5 million tons of plastic packaging had been generated (see Figure 3).

Figure 2: This graph demonstrates the exponential and unprecedented rise in plastic packaging (magenta), which includes disposable foodware, since 1960. Source: Jason Treat and Ryan Williams (2018), Planet or Plastics?, National Geographic (data sources are labeled in the graph). Please note that this site is behind a paywall. Click for full sized image.

The US and Berkeley experienced a rise in disposable foodware through increased prevalence in grab-and-go meals, takeout, and delivery for consumer and operational convenience. Disposable foodware was also being produced in various forms making it difficult to separate recyclable components from the majority of non-recyclable components. That meant that roughly 86% of the US. plastic packaging was landfilled or incinerated, and the remaining was recycled. However, this came with higher expenses for US recycling facilities, which were unable to manage the volume of new materials without investments in equipment and labor. Plus, there were little to no end markets for the sorted materials. Finally, the volume produced and disposal practices were even more alarming given that plastic packaging is only used for months and disposable foodware is only used for less than thirty minutes before being tossed.

China, the largest importer of US and international scrap plastic, adopted Operation Green Fence in 2013 which put heightened restrictions on acceptable materials. Then in 2017, China implemented Operation National Sword which all but eliminated the import of plastic scrap. This threw the entire global plastics trade system into disarray, especially as other countries adopted similar import restrictions upending decades-long export practices and sending the value of recyclables into a death spiral. Soon not only plastic but also paper and other products were completely worthless.Some states even began landfilling or burning them. By 2018, export markets for mixed plastic scrap were basically non-existent and there were no significant US markets forcing recyclers to landfill collected foodware and other non-recyclable plastics.

These factors combined spurred the team of local nonprofits, concerned community members, and the Ecology Center to convene. That team began by identifying the disposable foodware problem and subsequent action.

Figure 3: This graph demonstrates the total amount of plastic packaging generated in the U.S. between 1960 and 2018 in thousands of tons. By 2018, that cumulative amount was 14.5 million tons, roughly 29 billion pounds. Considering that plastic packaging is so lightweight (think of a plastic fork, or Saran wrap), this cumulative weight is astonishing. Source: U.S. EPA (2022), Containers and Packaging: Product-Specific Data (data sources are labeled in the graph). Click for full size image.

The Trouble with ‘Compostable” Foodware

In Berkeley, we were seeing the growth of disposable plastic foodware in real-time. The growth of unrecyclable plastic foodware was showing up in our streets, creeks, and shorelines. It was increasingly contaminating both our compost and recycling. We watched as our neighbors pushed into foodware substitution models promoting compostable foodware resulting in even more nonrecyclable plastics. Many of these new foodware product lines were potentially compostable but many others were either false ‘degradable’ options with petroleum content, plant-based but not actually compostable, or compostable but only under specific conditions. In addition, customers were increasingly confused about where to put them. For example, after large public events recycling, landfill, and compost bins had roughly the same contents.

Regional municipal composting facilities’ capacity had been expanding for about a decade, but getting new ones sited was extremely difficult so the existing sites were taking on ever more throughput. What once was a compost production system turned into a green waste disposal system. The original facilities’ business model was to get cheap feedstocks from agriculture, commercial landscaping companies, and some municipal yard debris to create high-quality, high-value compost. As more cities began separating yard debris, then food waste, the original goal and revenue source of selling compost changed to getting paid to dispose of municipally collected yard debris and food waste.

In those early years, most of the compost facilities processed compost over the course of about 180 days. By the time California’s groundbreaking compost law, SB 1383, was passed requiring 75% of all compostables to be diverted from landfills, most of these facilities changed to an accelerated 90-day composting process. While this increased the capacity and efficiency of these facilities, 90 days is rarely long enough to compost bioplastics.

Additionally, testing of these bioplastics showed that they degraded similarly to other plastics and produced many of the same problems in marine environments. Nonetheless, businesses had become attached to clear packaging to sell fruit salads, juices, and other visually enticing grab-and-go prepared foods. They claimed that moving away from plastic would be devastating for their businesses.

While paper and fiber-based foodware seemed like the best way forward in February of 2017, the Silent Spring Institute released a groundbreaking report on the extensive use of toxic and persistent fluorinated petrochemicals such as PFAS and PFOAs as a grease and water barrier on paper-based foodware, especially in those designed for composting. Subsequent studies found these chemicals in municipal compost resulting from high concentrations of compostable paper foodware.

End of Life

The first nested factor was local; disposable foodware was flooding the streets of Berkeley. This put large operational costs on the City for street sweeping, litter cleanup, storm drain maintenance, and compliance with the Clean Water Act. Furthermore, one business improvement district has employees and volunteers focused on routinely collecting litter. The litter not captured was ending up in local natural environments, creeks, and the bay, harming the flora and fauna. Other costs came through Berkeley’s transfer station where discarded material is sorted to be landfilled, composted, or recycled. Berkeley does not have a landfill or an incinerator, meaning the pollution impact of local disposable foodware goes to other communities.

Health Impacts

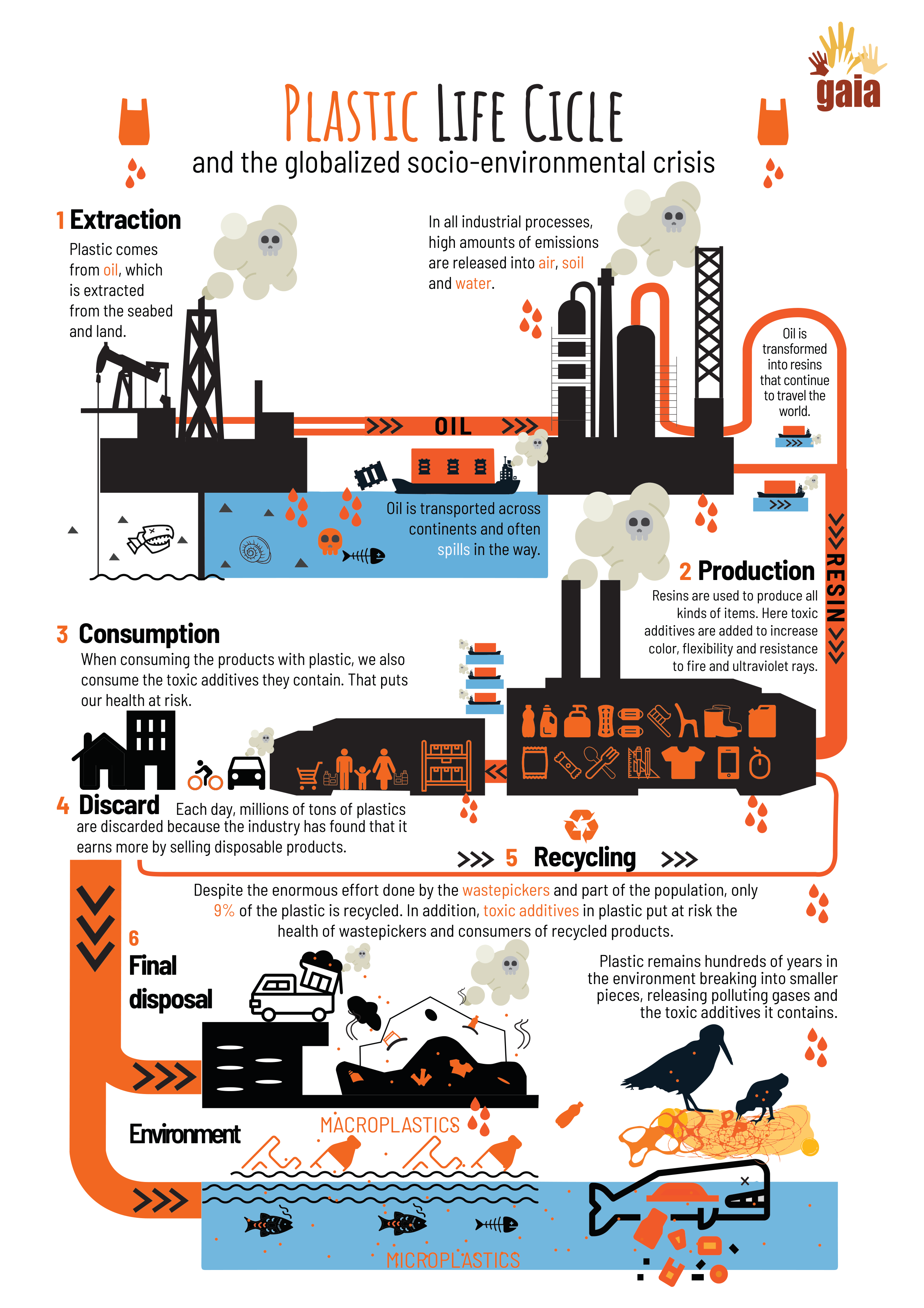

That brings us to the second nested factor: it was increasingly apparent that plastic disposable foodware has enormous environmental and human health harms, from “upstream” (extraction, manufacturing, transportation) to consumption to “downstream” (disposal). Please see Figure 4 for a visualization of this process. Upstream, the production of plastic is a highly resource-intensive process that relies on oil and gas extraction and refineries to make precursors and eventually ‘nurdles’, the feedstock used for plastic products and packaging.

Figure 4: This illustrated life cycle demonstrates the various environmental and social impacts of plastic production, consumption, and disposal. Source: GAIA, Plastic Crisis: Challenges, Advances and Relationships with Wastepickers.

Plastic production therefore depletes oil and gas, a non-renewable natural resource, and requires significant energy and water. Additionally, there are numerous health impacts on the people working in the facilities and living near those extraction and production sites or pipeline transportation routes. These communities have been called ‘sacrifice zones’ or ‘fenceline communities’ for the irreparable harm that has been placed on them over the years. These terms reinforce and normalize the idea that some people will have to suffer for the convenience of others and that plastic foodware is more important than people’s health and lives.

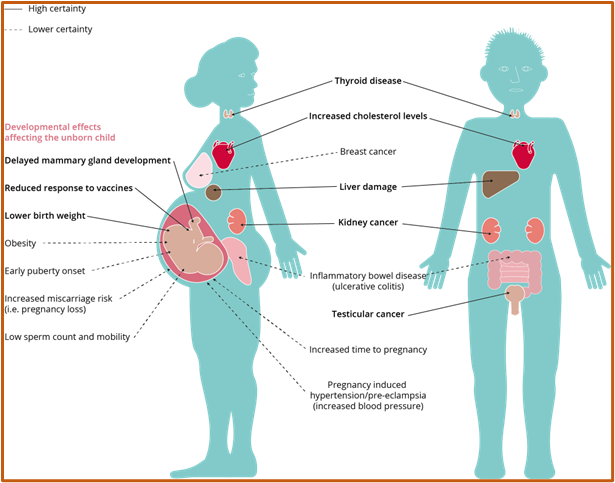

Figure 5: This figure demonstrates the human health effects of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, which are in plastic disposable foodware items and thus enter the body through the migration of those substances into the foods and beverages we consume. This graph does not capture the pollutants consumed through soil, water, and air pollution created throughout the other phases of the plastic life cycle (extraction, production, and disposal). Source: Suzanne E. Fenton, et al. (2021). Per and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Toxicity and Human Health Review: Current State of Knowledge and Strategies for Informing Future Research. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry.

During the consumption period, it is well documented that toxic chemicals can migrate from plastic containers to the food or beverage they hold, thus be ingested. The human health damage is not in that single exposure, but in the lifetime exposure and thus bioaccumulation of these chemicals that have unknown properties and interactions within the body.

Finally, like the upstream processes, the downstream processes impact both humans and the environment. The ‘proper’ disposal methods for plastics are recycling, landfilling, and incinerating. At the start of these discussions in 2016, the estimated US recycling rate was 9%. In early 2022, that rate was closer to 5%. The remaining 95% (or more) of US discarded plastic is landfilled or incinerated, domestically or internationally, or ends up loose in the environment. Both landfilling and incineration can cause soil, air, and water pollution, again harming the people working in those facilities and living nearby. Although Berkeley does not have a landfill or incinerator, we did not want to continue to contribute to pollution from disposable foodware to other communities.

Convening a Coalition and Proposing a Solution

Following the 2016 elections and the Break Free From Plastic strategy meeting in Bali, Indonesia, we gathered with leaders on plastic reduction campaigns from across the country at a small two-day strategic meeting hosted by Upstream. While the national elections were a disaster for the climate issues in general, at the local level Berkeley had just elected Mayor Jesse Arreguín and Councilmember Sophie Hahn who both included zero waste priorities in their election campaigns. At the gathering, leaders were discussing priorities and points of collaboration at the national level. As a local organization, we understood the importance of local place-based organizations modeling emergent strategies. We invited leaders from this group to campaign to pass a comprehensive disposable foodware reduction model ordinance.

Motivated by that initial meeting, the Ecology Center convened some of these leaders based in the Bay Area and local community members interested in and active on disposable foodware and/or plastics issues. During these initial multi-stakeholder discussions we agreed that a localized change in disposable foodware production, consumption, and disposal was needed. Below we describe that process from convening, to defining the problem, to identifying solutions, to organizing and taking action and to passing the most comprehensive anti-disposable foodware ordinance of its time. We frame it in a generalized theory of change to more easily convey what occurred, however, please note that it did not begin so methodically, but instead took a more responsive and organic approach.

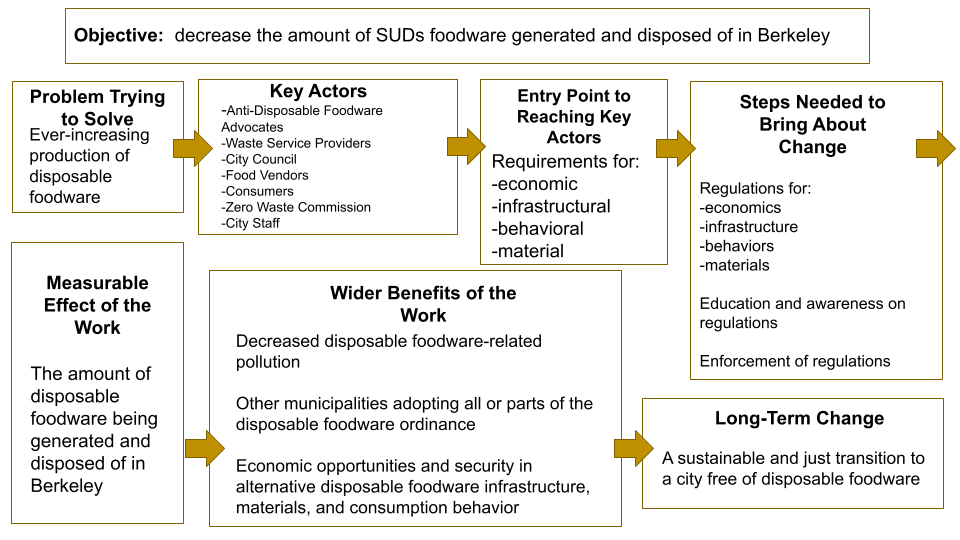

Figure 6: This is a diagram of the theory of change the Ecology Center and key leaders adopted as a guide for action to achieve the goal of passing the Single Use Foodware and Litter Reduction Ordinance. Source: The Ecology Center (2022).

The overall objective determined by the convening of key anti-disposable foodware actors was to decrease the amount of disposable foodware generated and disposed of in Berkeley. The measurable effect of the work to achieve that objective is the amount of disposable foodware being generated and disposed of in Berkeley. The wider benefits of the work through achieving that objective is:

- decreased disposable foodware-related pollution outside of Berkeley;

- other municipalities adopting all or parts of the disposable foodware ordinance;

- economic security and opportunities in alternative disposable foodware infrastructure, materials, and consumption behavior; and

- reduction of costs for local food businesses and city waste operations.

Finally, the long-term goals for change as a result of achieving that objective is a sustainable and just transition to a city free of disposable foodware.

Lessons from Plastic Bag Reduction Strategy

The anti-disposable legislative trend prior to the Berkeley ordinance was to make foodware compostable and/or recyclable; meaning that disposable foodware was still allowed – and in many cases encouraged – but it had to have better reclamation rates, better diversion-from-landfill (or incinerator) rates. For instance, when the plastic bag was banned, grocery stores and restaurants switched to recyclable or compostable paper bags. However, disposable carryout paper bags had other negative impacts on the environment, highlighting the problems with a substitution model. It became clear that the question should not be “do you want a plastic or paper bag?” but rather, “do you need a bag?”. Following the lessons learned in reducing disposable carryout grocery bags (both paper and plastic) and the #BreakFreeFromPlastic ethos we set the objective of this ordinance to prevent disposable foodware all together, allowing only the least impactful substitutes as a last resort and transitory step.

The objective of this disposable foodware reduction ordinance to prevent disposable foodware all together, allowing only the least impactful substitutes as a last resort and transition to a disposable free Berkeley

- Charges Work, but Don’t Make it a Tax. Making the cost visible does drive behavior change, but no one likes a tax. In California, if you want to create a local tax you have to pass a ballot measure. If you want to determine specifically how that tax will be spent, you need to win with a ⅔ majority. This was a major factor in selecting a charge-based structure. The bag reduction strategy works because customers can see the cost of disposables and that they pay for it.

- Let Businesses Keep the Money. Allowing grocers to keep the charge to offset any costs they might have in making the transition got the support or nullified the opposition of the grocery industry.

- Watch Out for What you Ask For (Thicker Bags). When making a new specification in law about what constitutes a ‘reusable’ bag the bag reduction laws drove both a reduction but also the use of marginally thicker reusable plastic bags. We wanted to make sure we did not have such unintended consequences in the disposable foodware reduction ordinance.

- Change the Question. For years the debate has been “paper of plastic, which is better?” With the bag reduction law we sought to change the question a checker would ask a customer from “paper or plastic?” to “do you need a bag?” This was tremendously successful and something we wanted to replicate: rather than “for here or to go?” We wanted baristas asking “do you need a cup?”

- Bring Your Own (BYO) Works. People said that customers would never bring their own bags and that grocers would lose business as a result. Neither was true. People quickly made the change, supermarkets put up signs in parking lots to remind you to bring your bag. We focussed on BYO cup as a key strategy.

- Stay Focused on Reduction. With the bag reduction laws, initially everyone was just trying to ban plastic bags. We learned from this effort that this can open you up to lawsuits and data battles about which is better or worse, and that it results in a massive increase in the use of paper bags. We learned to stay focused on reduction rather than substitution as a result.

We knew that not all vendors and consumers would be ready and able to transition to entirely reusable beverage and food containers. So, while the focus remained on reduction rather than alternative disposable foodware option – like the paper bag – it was imperative that a non fossil-fuel based disposable foodware option was also available. The Disposable-Free Berkeley team decided to advocate for BPI certified compostable disposable foodware.

Baseline Agreements and Understandings

A few additional guiding principles of the disposable foodware ordinance were that it was:

- Acceptable to food vendors;

- Feasible to pass, implement, and enforce;

- Built on the successes and learnings of previous anti-disposable legislation like our carryout bag reduction laws;

- Comprehensive so it could be used as a model ordinance for other jurisdictions worldwide.

Furthermore, a mantra throughout the process was that it needed to be adopted, meaning concessions would be made and it would not be ‘perfect’ ordinance from any single stakeholder’s perspective. One route for approval was making it an ordinance and thus voted on by City Council rather than a ballot measure that would be voted on. In California there are laws restraining the passage of new taxes that require a ⅔ vote by local voters. So finding a solution that was not a “plastic tax” was assumed as a basic premise.

Breaking Down the Work into Subcommittees

After identifying the desired output – an ordinance – we formed three subcommittees:a Legislative Committee, to work on drafting ordinance language and building support with the City staff, Council, and Mayor; a Business Outreach Committee, engaged in getting feedback and finding leaders to support the issue; and a Community Outreach Committee, to gather petition signatures, email lists, and promote our efforts via social and earned media.

The Legislative Committee

The Legislative Committee worked long hours looking at existing city language, state and federal codes, and exploring the existing foodware ordinances in other cities. They began to test the waters with key city departments: Department of Public Works, who oversees the stormwater and solid waste divisions; and Economic Development and the Environmental Health staff, who work closely with restaurants. These first forays exposed questions and concerns for us to follow up on, like the benefits of reusable foodware and how a disposable foodware free city could look.

The Legislative Committee worked closely with our champion on City Council, Councilmember Sophie Hahn. As someone passionate about waste reduction and meticulous about ordinance language, she authored improvements and revisions to the original ordinance language at each stage of the public process. As this was uncharted territory there were lots of variations of draft language crafted. Final drafts were reviewed by the legislative team in consultation with the broader coalition to ensure we could all still support the ordinance as it was revised based on broader stakeholder feedback.

Business outreach was extremely critical. While there were many forward thinking businesses already doing a lot to reduce foodware waste, there were also many small family run businesses operating with small margins and time tested practices and procedures. Strong opposition from the business community would likely have significantly reduced what was possible.

The Businesses Outreach Committee

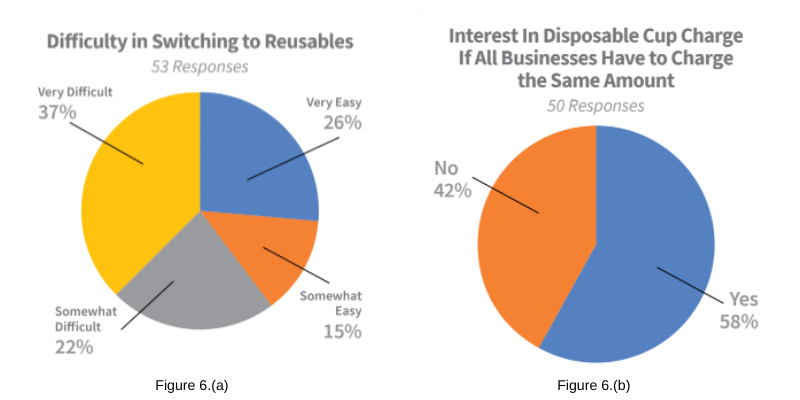

A subcommittee led by Clean Water Action’s Rethink Disposable conducted a survey on the food vendor’s needs and perspectives of such legislation. Those surveys demonstrated that nearly all food vendors saw some problem with disposable foodware and that 58% of food vendors surveyed were in support of a $0.25 disposable cup charge if they got to keep some or all of the charge (see Figure 6), if all vendors were required to charge it, and if customers were aware that it was a City-mandated charge. Additionally, the food vendors saw the value in reusables, but also saw the barriers to getting the necessary infrastructure in place. Finally, vendors were willing to accept filling customer’s personal mugs, but were generally not yet ready to accept customer’s personal food containers – a form of Bring Your Own (BYO) – because they thought it was too much of an operational hurdle, they were not sure if it was allowed by health code standards, and they feared difficulties in portion control, especially when creating meals quickly, or in advance for grab-and-go applications.

Figure 6: These data, compiled by Clean Water Action’s ReThink Disposable team through a survey of food businesses, demonstrate that (a) 37% of food businesses felt it would be very difficult to switch to reusables, and (b) 58% of food businesses were keen on having a cup charge if all businesses needed to comply with the regulation.

Source: Clean Water Action, Clean Water Fund (2018), A Policy Approach to Reducing Disposable Food Packaging and Litter: A Survey of Food Business Owners Berkeley, CA.

In addition to the survey, team members met with representatives from every Business Improvement District (BID) and the Chamber of Commerce to get their feedback. Initially the goal was to try to keep them from opposing but we actually got substantial support from them. In addition to representing businesses in their districts they are responsible for keeping the district free of litter, something they all spent a lot of time and money on.

The Businesses Outreach Committee helped promote the public listening sessions that the Zero Waste Committee held to local businesses, organized visits to concerned businesses with council members, and they secured key business spokespeople who would speak publicly about the benefits of reusable foodware.

The Community Outreach Committee

The Community Outreach Committee worked with the Oxford Elementary School Zero Waste Classroom to collect nearly 1,000 petition signatures at our local farmers markets. The committee pushed out the petition to the community via social media posts and at other events. The petition was very simple, stating that there was a real problem and asking the council to take action. This allowed the specifics of the ordinance to change without having to go back for new signatures as the content changed. Petition gathering also allowed us to build a strong email list to inform and cultivate supporters who could make donations, volunteer, or come out to speak in favor of the ordinance. This committee also worked with the Ecology Center communications staff to organize press releases and events. This committee led organizing our public comment during City Council when it came time for the final vote.

All of this feedback helped shape the draft ordinance and recommendations to staff. Changes included: running a reusable foodware pilot as an alternative to BYO, providing technical assistance and a mini grant program to support the transition to reusables, and omitting a $0.25 charge on food containers.

Introducing the Ordinance Language & Getting Stakeholder Feedback

In Celebration of Earth Day 2018, Councilmember Hahn formally introduced the ordinance into the City processes with a referral item requesting that the City Council refer the draft language to the Zero Waste Commission, and requesting that the Commission obtain public feedback and come back to City Council with recommendations on revisions. Over the next five months, the Zero Waste Commission, a citizen advisory body to the Council, held six public meetings and collected 65 pages of comments. The Commission ensured meetings were as accessible as possible by conducting them during different times of the day and different days of the week. Additionally, City staff undertook outreach efforts to ensure people were aware of these meetings. During the meetings, the Commission had different non-Commission representatives (the Ecology Center, Upstream Solutions, and a City Councilmember) explain why the policy was being developed, background on those particular solutions, and how the policy would be created and implemented. The comments from the meetings were consolidated into key findings and recommendations and submitted to Council on December 11, 2018. These recommendations formed the basis for key revisions in the final draft ordinance.

Challenges: Unanticipated and Anticipated

Before going into the specific components of the ordinance, there were a few key challenges that were both unanticipated and anticipated in both its drafting and advocacy.

Two large unanticipated challenges arose in the final stages of the ordinance writing period. The first was that Berkeley had recently adopted a Minimum Wage Ordinance taking minimum wage to $15.00/hr over 3 years. The final phase of this law went into effect in October of 2018, right when we were getting the recommendations for the commission back and preparing to go to council with the final version. This meant labor was a much larger expense for food businesses. A higher cost for labor drove food vendors towards less labor-intensive operations, such as counter-based service versus sit down table service. This, coupled with vendor and customer convenience drove an increased reliance on disposable foodware. Some businesses saw it as a bad time to potentially increase cost because of compostable foodware requirements and onsite reusable foodware requirements. Case studies from Rethink Disposables became very important at this time demonstrating that reusables actually save money even when taking into consideration staff time, and energy and water costs. However, in an effort to support businesses, the timeline was moved into three phases and a temporary exemption due to the hardship process was included.

The second unanticipated challenge was the pushback from the disability justice community. Early in the process we had reached out to many organizations representing members of this community. The issue was taken up by members of Berkeley’s Commission on Disability who spoke at public comment sessions about the need for plastic straws, but no formal suggestions, comments or recommendations were presented. Part of the disposable foodware ordinance mandated that foodware accessories – including straws – were not to be provided automatically, but instead by request only or at self-serve stations, and that the straws must also be BPI certified compostable.

There was a national discussion underway at the time regarding plastics straws and the need for them by some community members for health reasons in light of broader efforts to ban plastic straws. Spokespeople for this community had tested paper and compostable straws, and reusable metal, glass and plastic straws and found they did not serve their needs. Unfortunately, attempts to bring representatives from this community into the fray were unsuccessful and it was not until the final days before the item was to be voted on that they came forward. After several key phone meetings with their spokespeople and Councilmember Hahn, coalition leaders were able to agree on language suggesting that businesses keep plastic straws on hand for customers who might need them.

Interestingly, a challenge that the disposable foodware ordinance team prepared for but did not experience was strong pushback from industry (e.g., fast food companies, the restaurant associations, plastic manufacturers, chemical companies). This is due to the nuanced political environment of Berkeley, California. Berkeley has both strict campaign contribution limits and zoning limits that favor small businesses. For campaign limits, no single entity can contribute more than $250 to a campaign, meaning a large food chain can not easily use a well-funded lobby group to apply political or financial pressure on Berkeley’s elected officials. Councilmembers can listen to these lobbyists, just like they would listen to all constituents, but they have much less leverage in our community. Furthermore, the zoning greatly favors small local businesses – effectively creating a fast food moratorium over the years – and Councilmembers’ constituents are predominantly opposed to fast food chains. Councilmember Hahn, the author of the disposable foodware ordinance, still met with representatives from McDonald’s and restaurants, but did so without the pressure that they could be a player in the next election supporting her if she did what they wanted, or funding opposition to oust her if she did not.

Additionally, the plastic industry and other large fossil fuel companies are considered by many in Berkeley to be inherently bad actors with no credibility. Showing up in force to fight this battle in this city could only be bad for them and would likely backfire. So while some industry reps sent in comments and sought meetings with Councilmembers to propose changes to the proposal, they did not come out as directly opposed.

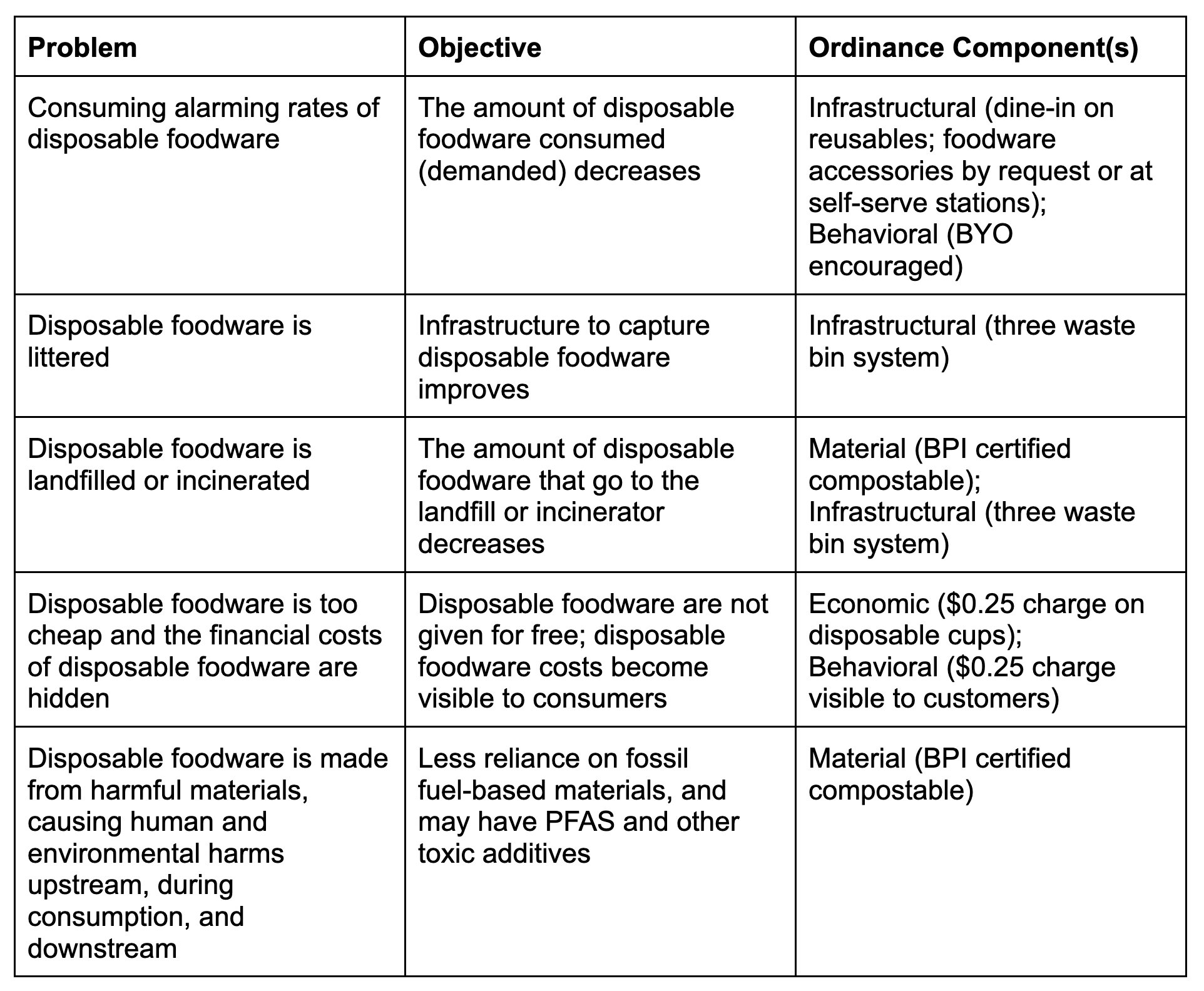

The Final Ordinance's Components and Why

The Single Use Foodware and Litter Reduction Ordinance is at the heart of the Theory of Change; the component for which all actors focused, all steps were taken, and all measurements were based on.

Below we first outline the components of the ordinance, highlighting the aspects that made it historical. Then we map the components back onto the original problems and objectives to demonstrate why it was built in that manner.

There are three phases of the ordinance. Each phase had a different enactment date, then had an enforcement date starting one year later. The intention behind the delayed enforcement date was to give all stakeholders an adjustment period, be it operational, economical, or behavioral.

- Phase one: enacted immediately upon City Councilmembers’ approval (January 22nd, 2019); enforced January 22nd, 2020

- Foodware accessories provided by request only or at a self-serve station

- City must purchase/ use reusable/ BPI certified at facilities and City-sponsored events

- Three waste bins for vendors with self-bussing

- BYO is allowed but vendors can refuse to accept

- Phase two: enacted January 2020; enforced 2021

- BPI certified compostable for all vendors

- $0.25 cup charge

- Charge visible on menus, signs, receipts

- Waivers available for disposable foodware alternatives

- Phase three: enacted July 2020; enforced July 2021

- All dine-in must be on reusable foodware

- Technical assistance, mini-grants, hardship waivers available

Compliance

From the start, enforcement was structured in the ethos of community-based development: enforcement was meant to come on gradually with no harsh sticks. If a resident or public official takes note of a food vendor not complying, the City sends them a notice of non-compliance. The vendor then has the opportunity to remedy the situation or apply for a hardship waiver. If the non-compliance continues, the vendor will be fined.

The ordinance impacts all vendors that sell food and/or beverages. This includes:

- coffee/tea shops,

- bakeries,

- farmer’s markets,

- food trucks,

- taquerias,

- fast food/fast casual,

- gas stations,

- and theaters.

This does not include:

- manufacturers,

- schools/ universities,

- and, areas that provide food but do not sell it (e.g., religious spaces or soup kitchens).

The ordinance does not overtly exclude fine dining establishments but since they do not have the conditions for which the mandates are required (e.g., no self-bussing, no disposable foodware given, all reusables), they are inherently excluded. However, during COVID those fine dining establishments began using disposable foodware as they shifted to take-out, thus requiring them to follow the disposable foodware ordinance regulations.

Passing the Ordinance

The final language eliminated the charge on containers, had a three year phase in and added an exemption process. The council Item also included:

Later that year, in December 2018, the City posted an online survey (“Berkeley Considers”), giving an additional venue for the public to review and comment on the draft ordinance. The City received 112 responses, with 75% supporting the proposal.

During the weeks and days before the item was to be heard, the reality of the ordinance’s potential passage became more tangible. So restaurants and other stakeholders who had not yet been involved became more active. Through the Business Improvement Districts, efforts were made to postpone the initial hearing of the ordinance to give them more time to discuss it and to give businesses another chance to make their voices heard. Due to these efforts and the other items on the council agenda in December the item was delayed and moved to January.

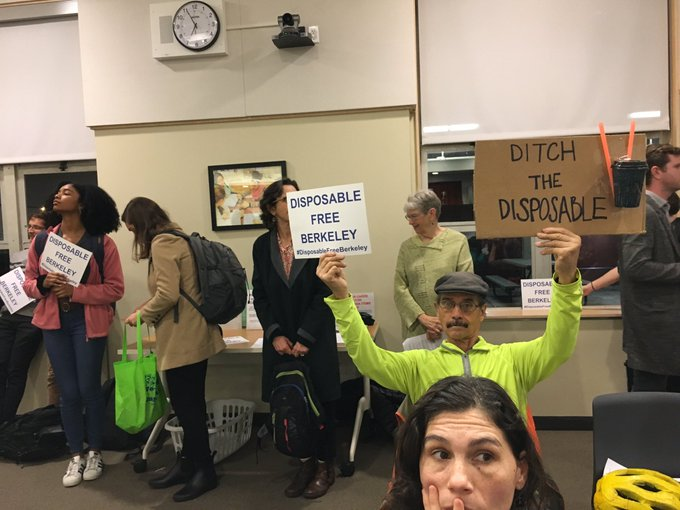

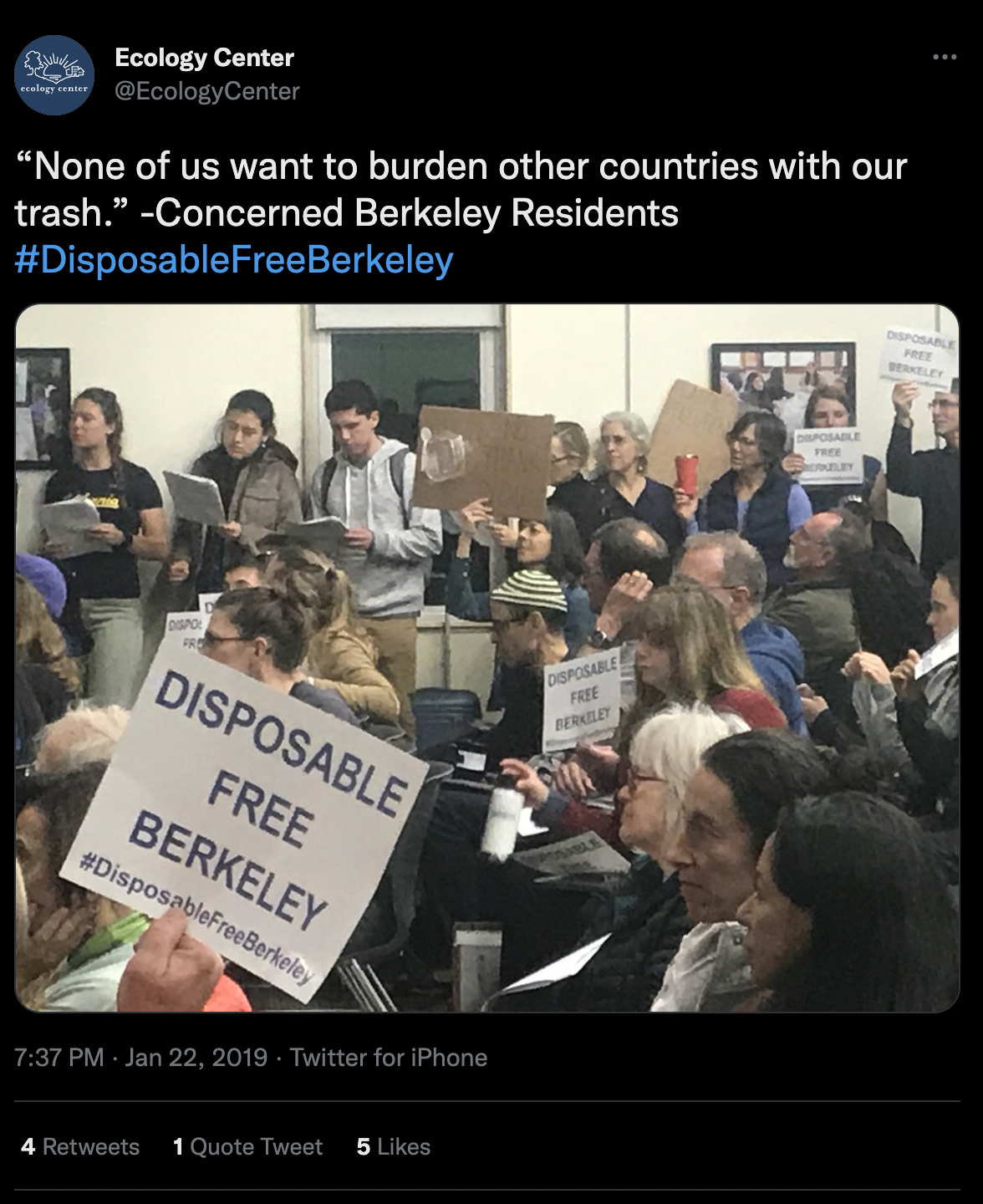

At the January 22nd, 2019 City Council meeting, residents, activists, and food business personnel from across Berkeley and the Bay Area showed up to advocate their support for this unprecedented comprehensive anti-disposable foodware legislation. Members of the audience represented over 1,400 advocacy organizations from local to international jurisdictions, and the comment period of the meeting lasted for almost two hours. The ordinance was passed unanimously.

Lessons Learned

Below are some key takeaways from our experience in creating and passing Berkeley’s Single Use Litter and Foodware Reduction Ordinance.

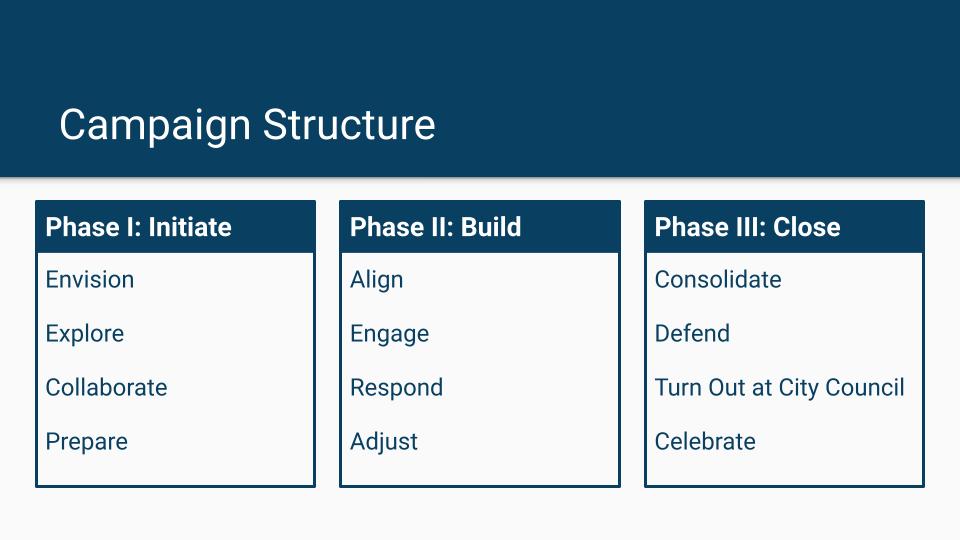

Campaign Structure

There were three phases to the campaign structure: initiate, build, and close.

Initiate included envisioning the desired outcome, which was done through numerous meetings with passionate advocates in the region. From there the team explored different policy options and gathered research as well as collaborated with key people who would support and reject such policy. Then the team prepared to build the policy and receive feedback.

The next phase, build, began with the larger team of advocates and key people to align on the purpose and objectives of the campaign. Then the team engaged stakeholders potentially impacted by such an ordinance, such as food business owners, low income customers, and the disability community. The team responded to feedback by adjusting the ordinance language accordingly.

The final phase, close, was consolidating all feedback and objectives into one cohesive policy that has a chance at being passed. From there, the team defended the various aspects of the policy and had a remarkable turn out at the city council meeting where the vote was made. Then, the team celebrated the victory of the unanimous passing of the ordinance.

A few things that particularly stuck out as learnings in this process:

- Have a multidisciplinary team that knows the nuances of the municipality and where members can form subcommittees to work on the various items

- Engage all stakeholder groups early, including but not limited to: city council, food vendors of varying sizes, disabled community, waste service provider; the Zero Waste Commission, which were unelected community members advising the City was key to coordinate and manage this process

- Figure out which council members are in opposition and do a cost savings analysis for their district

- Connect earlier with a councilmember to gain them as a ‘champion’

- Determine priorities and know when and where to negotiate

- ‘Victory’ can look and feel different than originally intended, for instance, having the Chamber of Commerce not in complete opposition – even if they do not fully support the initiative – can be a big win

More Granular Policy Items

- If a charge is put in place (e.g., a disposable cup charge), it is important to have a reusable cup/ food container system in place to provide a waste-free, equitable alternative. Local providers in Berkeley include Vessel and DishJoy.

- Create a directory of resources for food vendors including acceptable disposable foodware, reusable cup/ food container system providers, dishwashing providers, grants to transition to reusable foodware (e.g., purchasing the foodware, purchasing a dishwasher).

- Ensure that waivers (e.g., hardship waivers, low-income waivers) are built into the ordinance.

- Ensure support (or at least not opposition) from City’s zoning, permitting, and public works departments.

What Made it Work in Berkeley

Through strong community-based activism grounded in numerous nonprofits, we were able to mobilize a team of varying expertise and roles to strategically build, write, and pass this historic ordinance. These actors and passions are not unique to Berkeley, meaning implementing waste-free solutions in any jurisdiction is feasible.

What was unique to Berkeley was the supportive leadership from the local government (both a City Councilmember and the Mayor) as well as the inability for corporations to sway local elections. This separation of corporations and government is through a $250 maximum contribution limit to any election from any entity, Councilmembers required to report financial contributions received, and all lobbyists have to register and report all lobbying activity.

Concessions

Know when to make concessions. For instance, we prioritized having a disposable charge on cups and conceded a charge on food containers, with the negotiation that a disposable food container charge would be considered after a few years of the disposable cup charge in place.

FAQs

I want a policy in my community to decrease disposable foodware, where do I begin?

Fantastic! Starting can seem daunting, but it doesn’t have to be. We answer a few more specific questions below, but also consider reading our story on how we began, built, and passed such a policy in Berkeley, California which we describe above under “Finding a Solution”, “Process of Making and Passing the Ordinance”, and “Ordinance Components”. The recorded presentation under “Resources” also gives a high level review of the process (it is ~26 minutes).

What are some state and federal policies for reuse?

There are multiple types of policies for reuse, such as ones that prohibit single-use or foster reuse. Upstream has a comprehensive and updated list of policies across the world, which can be found here.

Policies that prohibit single-use include bans on materials or items or taxes/ fees on materials or items. Policies that foster reuse include requirements for all food and beverage consumed on-site at a food business be on reusable foodware.

What are benefits of a disposable cup charge?

A disposable cup (and/or container) charge can be an effective policy mechanism to reduce the amount of disposable foodware waste generated. See a four-page overview of these benefits here.

What are the benefits of reuse?

Reuse benefits span three fields: environmental, economic, and social. Briefly, those benefits include a reduction in pollution and carbon emissions, food businesses decreasing their costs and city and taxpayers saving money on litter removal and waste services, and less harm to communities near plastic production and disposal sites and more sustainable career opportunities. More on the benefits of reuse can be found here.

How can I become involved?

- Identify what organizations/ institutions in your community (if any) are already working on this and reach out to support them. This might include working with key stakeholders, such as city staff, food businesses, or consumers.

- Consider joining Upstream’s Skip the Stuff network to campaign for policies in your community.

- Support reuse services and those who adhere to the ordinance.

- Learn about your city and state policies, especially if there are any “preemption” laws that forbid policies to put a ban or tax/fee/charge on certain materials.

- Download and use the app, Remark.eco, to encourage businesses to be more sustainable.

- Depending on your job, you can find ways to foster reuse through your role and/or within your organization.

Do you have a template or other resources I can use?

We do not have templates, but Upstream does. Please visit their Community Coalition or Roadmap to Reuse site or email their Reuse Communities Policy and Engagement Officer, Macy Zander, at macy@upstreamsolutions.org. We do have an array of resources that can be found below under “Resources”.

We advise using one of these policy templates, modeling it off Berkeley’s ordinance, or working with municipal staff to write the ordinance.

What is an ordinance?

An ordinance is a law or decree by a municipality. Put differently, an ordinance is a local law. Usually ordinances forbid or restrict some type of activity. Ordinances are voted on by city council members versus the public.

What is a generalized timeline to create such a policy?

The amount of time it might take to create a policy varies substantially by jurisdiction. Factors that can increase or decrease the speed of creation include what sort of zero waste actions and coalitions are already in place, how active the public is in engaging the public and food businesses to co-create the policy, how receptive the governing body is such policy, and what sort of preexisting conditions and relations are in place. For Berkeley, which as a city was arguably more inclined towards such a policy, it took about two years from the first meeting of brainstorming policy actions to the City Council unanimously passing the ordinance.

City Council Documents

Official City Council Documents

- Referral to the Zero Waste Commission: Single Use Foodware and Litter Reduction Ordinance (4/24/2018)

- Item 16a – Commission Referral Response Single Use Disposable Foodware (12/11/2018)

- Item 16b – Staff Companion Report Referral Response (12/11/2018)

- Item 27 – Councilmember Hahn’s Revised Supplemental Packet 1 (12/11/2018)

- Item 27 – Councilmember Hahn’s Revised Supplemental Packet 2 (12/11/2018)

- Full Ordinance Language (1/22/2019)

- Item 22 – Single Use Disposable Foodware (1/22/2019)

Public Support

Social Media Campaign

View our media plan here!

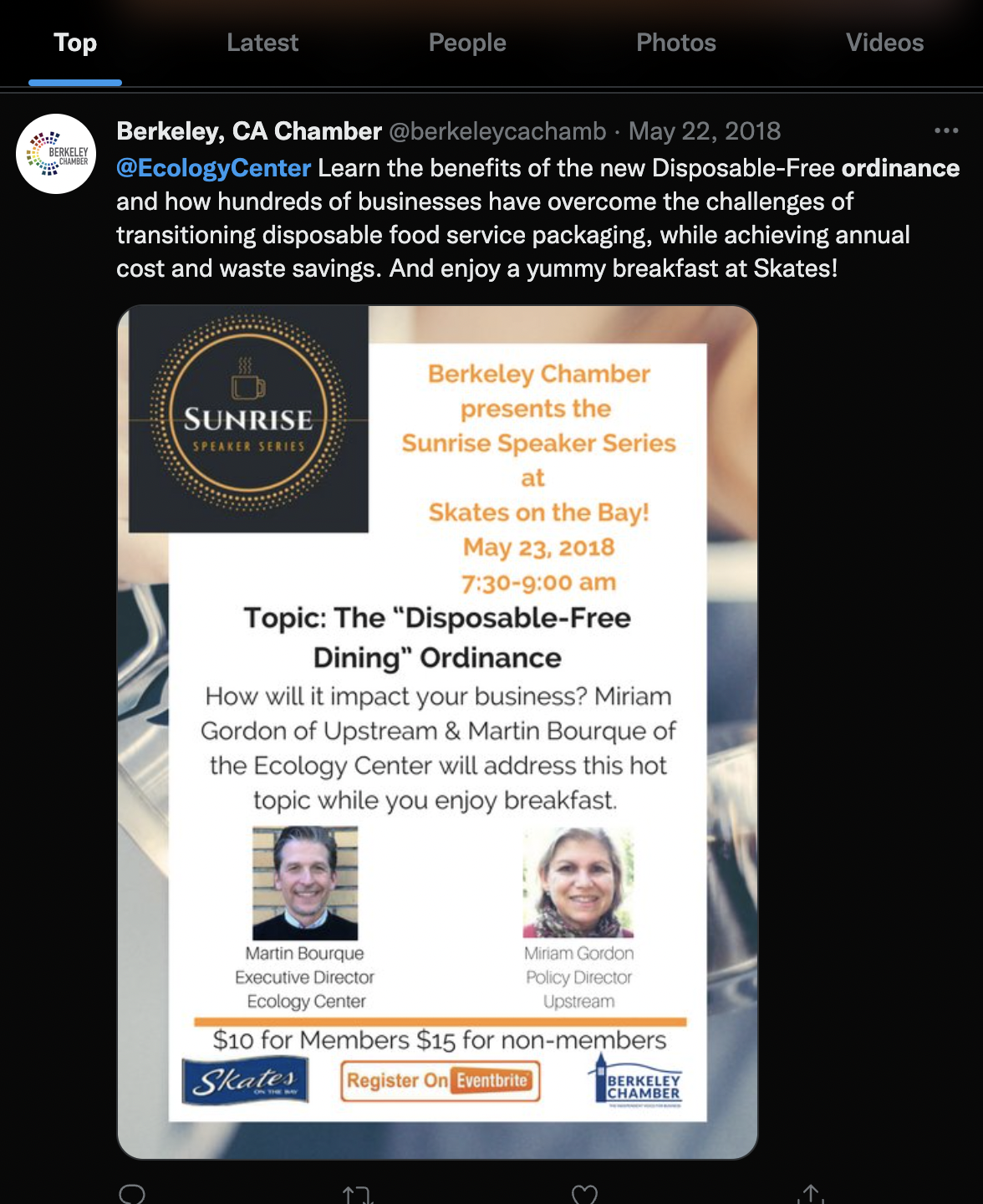

Early on in the campaign, the Ecology Center partnered with Upstream Solutions to hold a speaker series to connect with local businesses about the ordinance.

The Ecology Center used social media for calls to action, especially around inviting the public to share their voices for important decisions such as at Berkeley City Council meetings. Additionally, tweets share photos with the aim of getting more folks to join in the work.

The Ecology Center retweeted coverage of the meeting by local non-profit news source, Berkleleyside.

The Ecology Center retweeted coverage of the meeting by local non-profit news source, Berkleleyside.

Mayor Arreguin showing his support for the ordinance by tweeting about its historic signing.

Press Kit

Press Coverage

Local Bay Area news channel KTVU news segment in advance of Berkeley City Council’s vote.

KTVU covers Berkeley City Council’s unanimous adoption of the Single Use Foodware and Litter Reduction ordinance.

- From policy to practice: 4 years of the Berkeley Reuse Ordinance, The Indisposable Podcast, Upstream, March 2, 2023

- Opinion: It’s time for Berkeley to lead again – to save our oceans and planet, Berkeleyside, Councilmember Sophie Hahn, January 22, 2019

- Berkeley approves 25-cent fee on disposable cups at restaurants, Los Angeles Times, Associated Press, January 23, 2019

- Council To Vote On Ambitious Disposable Foodware Ordinance, SF Gate, January 22, 2019

Other Resources

Webinar

Sample Communications

- Disposable Foodware Ordinance Background & Justification (2017)

- Disposable Foodware and Litter Reduction Ordinance Summary (2017)

- Sample Coalition Agenda

- Disposable Talking Points & Counterpoints

- Draft email for letters of support from organizations

- Petition to Berkeley City Council

- Initial Draft Ordinance Language (2018)

- Letter to Berkeley City Council (post approval)

- Single Use Disposable Foodware and Litter Reduction Ordinance FAQ (2019)

- General Single Use Foodware Talking Points and Counter Points

Factsheets, Guides, and Reports

- How to Reduce Take-out Packaging Litter and Save Money, Upstream

- It’s Time to Say Goodbye to Single-Use Plastic Foodware, Marin County, CA

- The Dirty Truth About Disposable Foodware, Ellie Moss and Rich Grousset for the Overbrook Foundation

- Resuable Food Serviceware Guide, ReThink Disposable

- A Policy Approach to Reducing Disposable Food Packaging and Litter, ReThink Disposable

Get Started

- Roadmap to Reuse, Upstream

- Reusable Food Serviceware Guide, ReThink Disposable

- Hold the Plastic Please, Beyond Plastic